The GEN Z Series travels all across the continents from the University of Minnesota to the NUS – National University of Singapore to meet one of the brightest landscape architects in the younger generation. Hailing from Gujarat, India – Ekta Rakholiya recently completed her Masters in Landscape Architecture from the NUS.

Ekta is a nature enthusiast from her early upbringing and love towards being pampered by her grandma in a small village around Gir forest. She spent a lot of time playing in her grandma’s huge courtyard full of roses and various herbs. Ekta reminisces fondly, “Memories of walking to our farm, plucking tamarind flowers from trees and sleeping under infinite stars on breezy summer nights was truly divine. My childhood experience in nature has had a greater impact in my life.”

Her academic quest has seen Ekta Rakholiya learning at CEPT University in Ahmedabad, Technische Universiteit Delft in the Netherlands and National University of Singapore. She did her internship at the CC – EASE, HSLU – Competence Centre for Envelope and Solar Energy in Switzerland. She learned a great deal about passive solar-heat housing and building artificial glaciers in the cold desert of the high-altitude of Himalayas by joining the NGO – Ladakh Ecological Development Group.

Ekta Rakholiya talks to Johnny D about her exploration and interesting journey into the architectural world, and her insightful project ‘Beyond the (De) fence’.

Your childhood ambition, did you always wanted to become an architect?

I am the first ‘Architect’ in my family. As a child, I did not even know about the existence of architecture as a profession. I studied in Air force School. Naval Officers visited our school to brief students about career opportunities in Indian Navy, when I was in the ninth grade. For the first time, I heard about ‘Naval Architecture’. They informed that it trains us to be ‘Jack of all trades and master of none’.

Being a curious student, who loves science, geography, archeology, painting and sketching – the last sentence caught my inquisitive mind. My search disheartened me, because women can join Indian Navy only after graduation. However, the second word ‘architecture’ caught my imagination and I was drawn towards it.

Please write briefly about your University and Masters’ course.

I completed my Masters in Landscape Architecture from the National University of Singapore. The two-year course is Asia-centric and emphasizes urban issues. It was great to learn about the tropical forest system and the latest digital tool to analyze large-scale landscapes. Because of the pandemic, I missed a lot of learning opportunities.

Briefly describe your project.

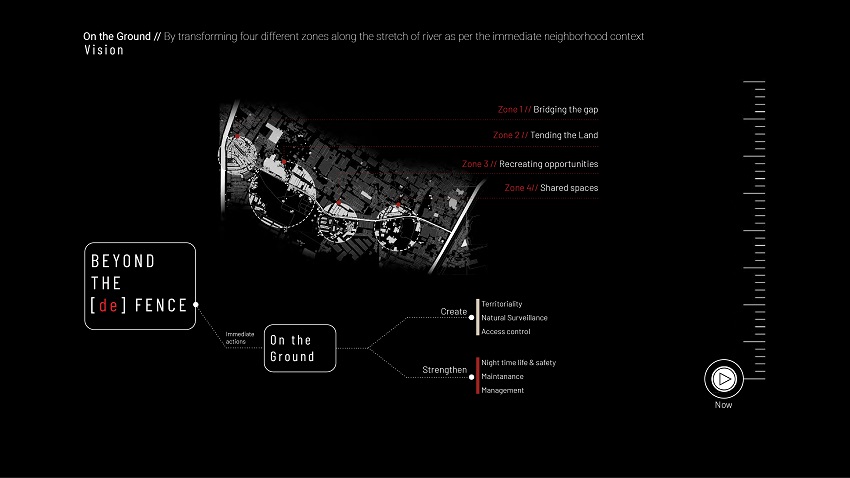

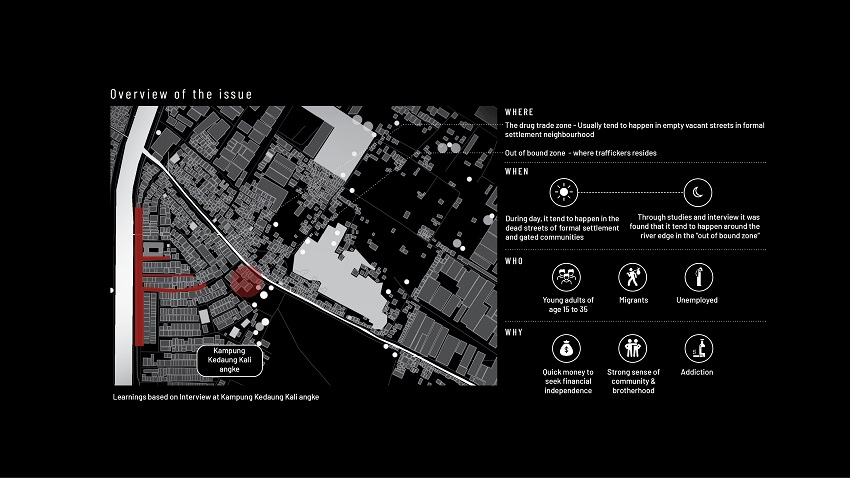

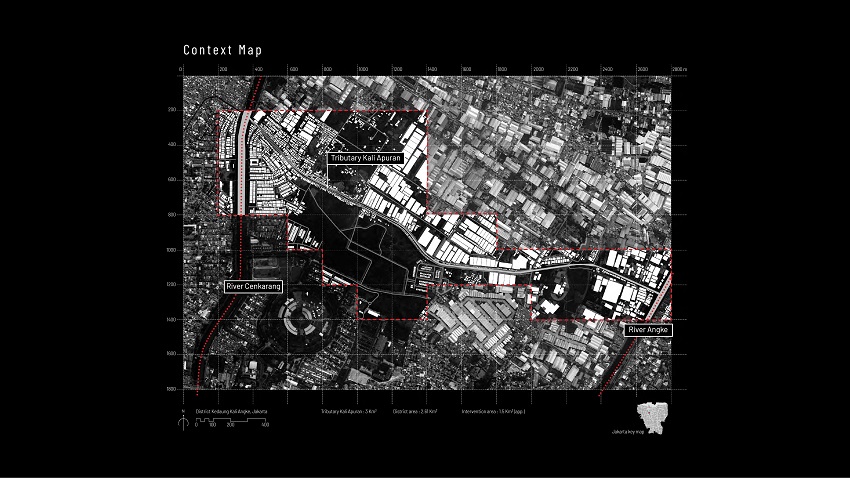

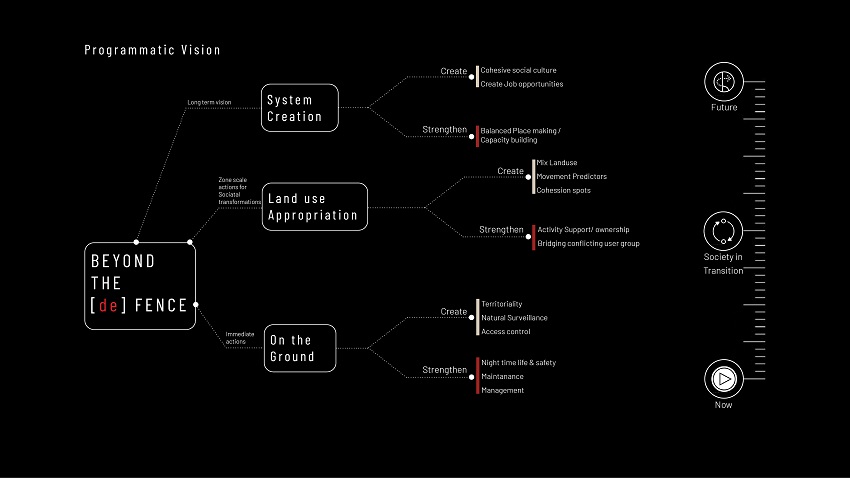

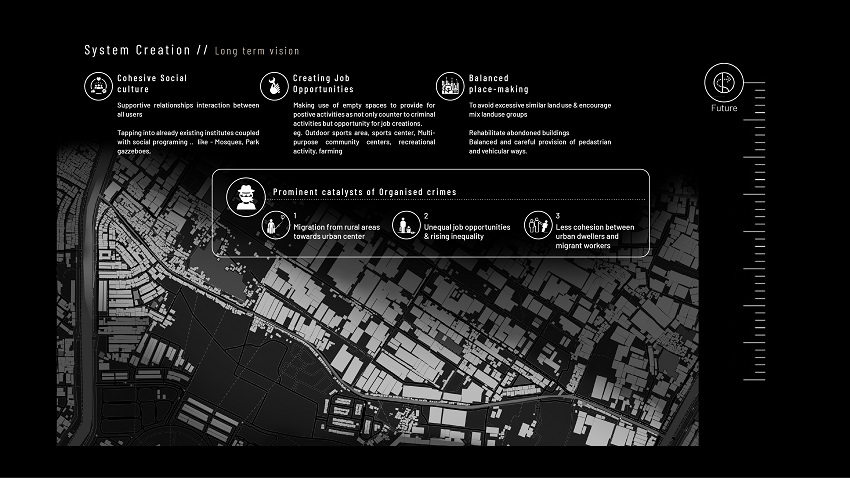

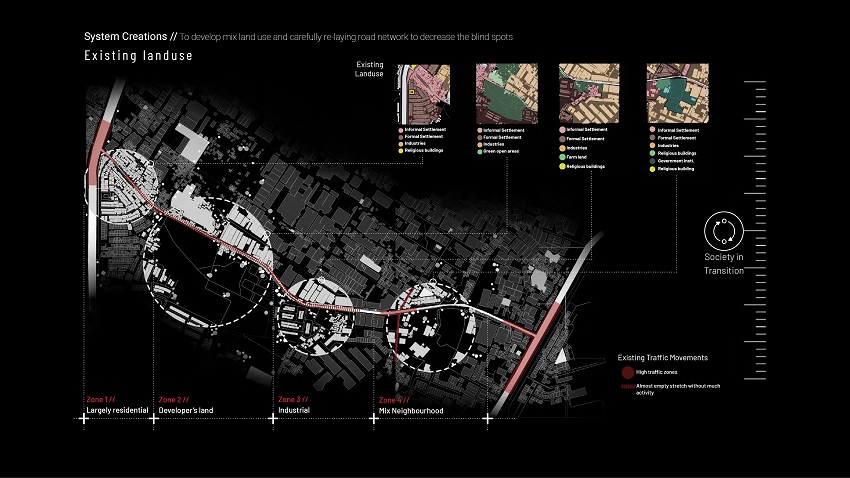

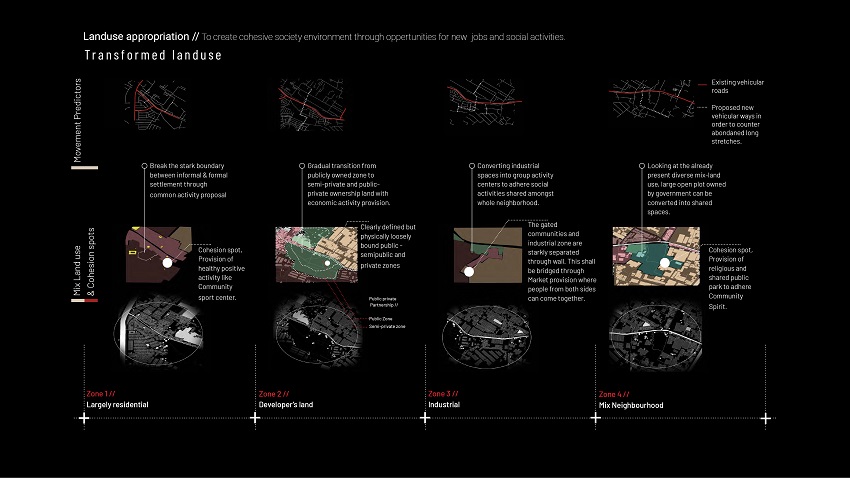

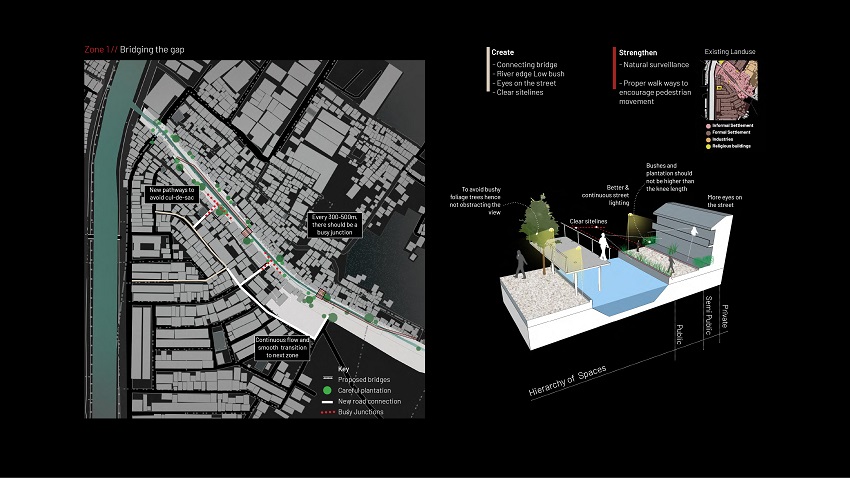

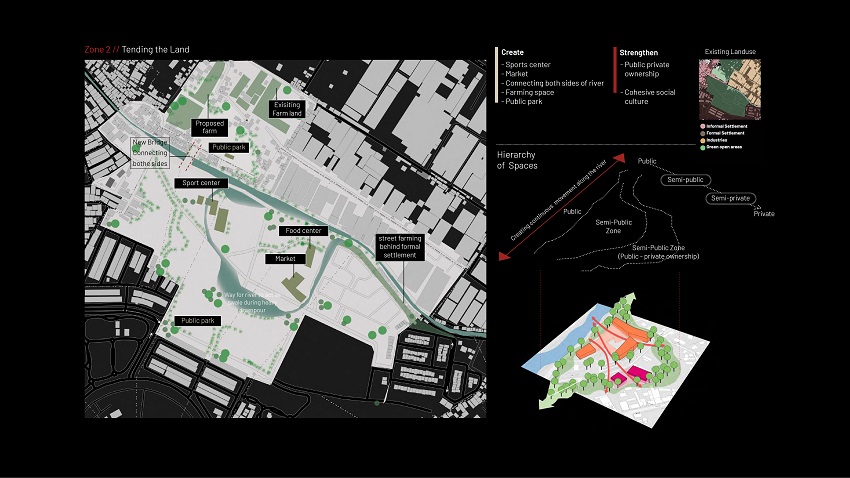

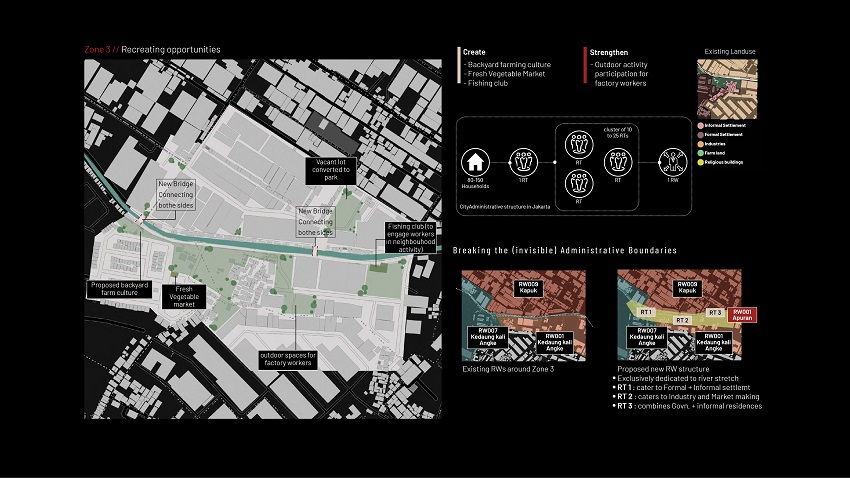

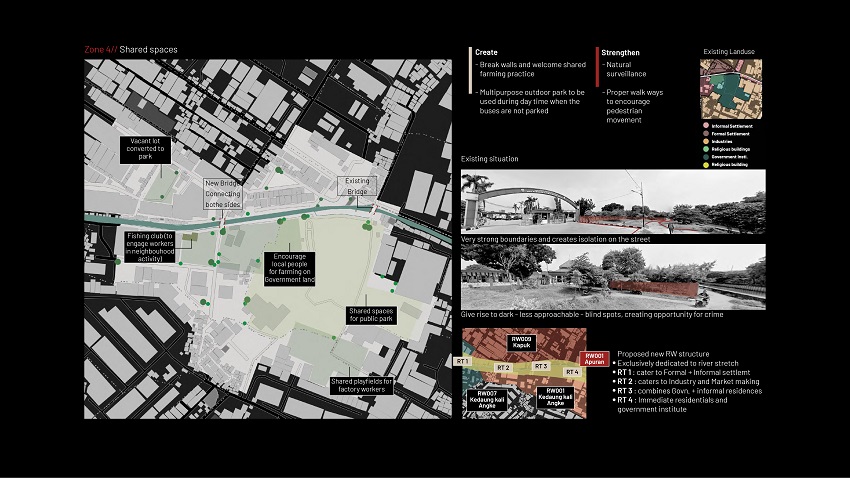

As the title suggests, the idea is to explore the concept of ‘Fence’ – “the notion of boundary” and (de) fence, i.e. “(through landscape intervention) un-fencing the boundary” to defend against crime. The project is about responding to the rapidly rising organized crime in Jakarta – especially the drug trade and narcotics – to transform the four zones around river Kali Apuran.

The aim is to re-appropriate river edge land use to create systems that not only deter crime, but also make a gradual transition towards a healthier social transformation. This is done through three major strategies borrowed from the theory “Defensible spaces: CPTED – Crime prevention through Environmental Design”.

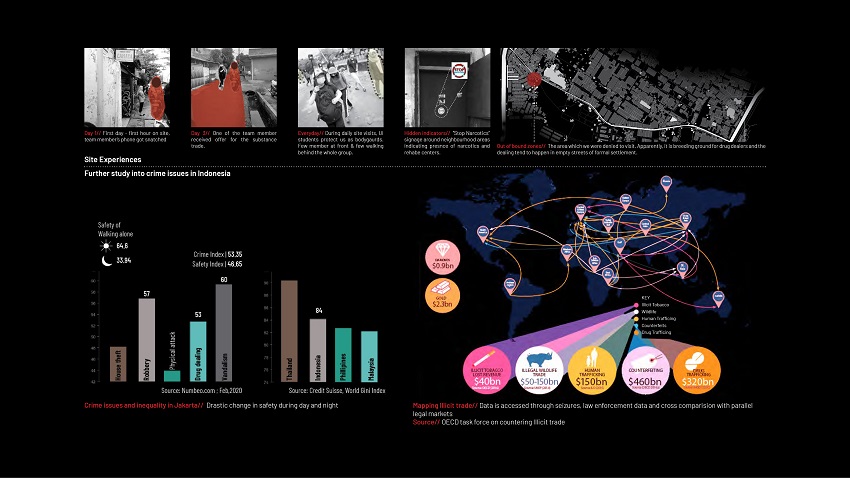

The project concern was based on personal experiences during our site visits. We experienced theft incidents and saw the presence of rehab centres. I learnt that Indonesia will soon rival Europe as a provider for the world’s illegal trade of crystal Meth. This indicates a high presence of organized crime in the country.

I believe that the solution to this lies in the way we design our urban landscapes. The proposed design interventions attempt to act as a circuit breaker of smuggling activities in urban centres by creating better opportunities for social well-being.

What does ‘architecture’ means to you?

I believe that ‘Architecture’ is a vehicle for our existence and collective transformation through which our society physically operates. It is an art and science of shaping our surroundings. We often do not realize but after food and clothing, shelter is our third crucial basic need that subconsciously shapes our habits, behavior, social structure, and eventually what we are as an individual or a society. Though being a student of Architecture is vastly different from actually practicing it. Perhaps there is too much idealism and we tend to forget the realities of what our job is, and how tiny our role is as architects.

In the end, it is a service that operates under stringent market forces and laws which are often out of the architects’ control. However, many projects make genuine attempts to bring a positive transformation in the society. It is generally perceived (and mostly operates) for lifestyle statement service to signal status and wealth. I believe that the profession needs a radical revamp to face the unprecedented challenges that the 21st Century is going to throw at us.

How has it influenced your life as an architecture student?

Well, it has influenced me in good and bad ways. The good part being, the immense gift of never-ending city explorations and constant contemplation on how we live. One of the unique things about studying architecture is that you learn to observe / experience spaces, places and people in a nuanced way. In the first three years as a student, I got to visit many remote villages in India for manual documentation or field trips.

In the fourth year, I got to live in Europe for more than a year as an intern and exchange studies student, during which I extensively traveled and explored new cities every other weekend. After finishing my final year, I joined an NGO in Ladakh and learned a great deal. I do not think I would have gotten the chance to explore countries in my formative years, if I was not a student of architecture. The sheer length and breadth of diverse experiences I have had in these six years were transformative.

The negative aspect is that working in an architecture firm is very different from a student’s life. Intense work and sleepless nights took a huge toll on my health and sleep cycle. I still remember not sleeping for almost thirteen days in my second year. I would take power naps on my desk with my head down and then immediately back to work when I wake up. Eventually, I learned to do my work in a better way.

I approached my Masters with a self-pledge that I will call it a success, if I can have an organized routine, exercise regularly and eat healthy home-cooked meals (smiles). While the first two semesters were challenging, by the time I graduated, I could go for a 5K run thrice a week, ate healthy food, was quite organized and my work efficiency improved drastically. The worst brought the best in me! So even the negative aspect is a positive one, I must confess (laughs).

Which Indian or International architect has inspired you? Please specify as to why?

This is a big one, because it is not just one but a mix of many. Peter Zumthore –for his sense of time and strong work ethic; Lauri Baker – for his service to the underprivileged; Chitra Vishwanathan – for place-based climate responsive solutions and being far ahead of her times (in terms of bringing down the energy consumption of the building); Franz Fueg – for sensitivity to materials; Frida Escobedo – for unique urban solutions; Suad Amiry – for her resilience and fierce work to repair and resurrect war-torn cities of Syria;

Paul Hawken (environmentalist) – for tremendous foresight on our climate issues and bold proposals for mobilizing climate actions; and finally, India’s legendary architect B.V. Doshi – for connecting people with spaces and for providing me a transformative journey at CEPT. At CEPT, I learned about ‘how to learn’ and ‘how to be a student of life’ –something that I realized only after I finished my studies and stepped out of the campus.

How has the pandemic changed your learning process since the last two years?

In terms of the creative process, it has drawn my attention towards writing and how it helps to achieve clarity faster. I also learned better ways to manage projects through project management software. Interestingly, the pandemic experience has helped me to appreciate ‘pause’ and contemplate.

For a person like me, who is actively jumping from one thing to the next it served as a good breather. I definitely became more organized and I could prepare my own meals. I learned to manage work along with taking care of self. However, with all its uncertainty, it is sometimes nerve-wracking as well, because the future is unclear and far more unpredictable.

What are your views on Climatic catastrophes and how architects of the future (your generation) will overcome the herculean challenge?

I desperately want to be optimistic but again and again, data has made me pessimistic. Studying landscape architecture made me one step closer to understanding how serious and urgent climate issues are and how hopelessly ‘nonchalant’ we are about it.

Architects, Landscape Architects and Urban Planners have the right knowledge and tools to help solve a few of the climate issues, but all of them are gravely limited in terms of their outreach. The profession operates under capitalist market mechanisms, which favor short-term gains over long-term solutions. It drives the whole profession in ‘let’s get it done fast’ mode.

The process of creation involves simultaneous destruction. To build a house, one must destroy some mountain or forest somewhere, take advantage of laborers to do the job of mining the material, transport it to distant urban centers, sell it to dealers who determine its selling price, and then eventually crafted or molded (again by laborers) to finally use it as a part of the house. It is a long arduous process and current market mechanisms are out of architectural profession’s reach or influence.

Unless a rapid large-scale systemic change is brought in all the sectors of the construction industry and unless we do not create a new economic model that takes long-term solutions into account, we are bound to keep continuing the current chain of destruction and head fast-track towards catastrophic disaster.

Please mention about ‘Honors and Awards’ you have achieved during your academic years.

– Honorable mention at Designing Resilience in Asia Participant at Bienal Internacional de Architectura de Sao Paulo;

– Runner up in Competition – Black Taj;

– Best Performance in material studio;

– CEPT University Best model maker of the year;

– Best Performance award (Design studio and Building Construction)

Image Courtesy: Ekta Rakholiya